Disasters are impacting the lives of millions of people around the world more than ever before. In the twenty-first century, there has been a significant rise in the number and intensity of natural disasters, such as floods that cover entire cities or earthquakes that destroy communities in an instant. these hazards are natural occurrences, the impact they have is greatly influenced by human decisions and societal actions.

Choices regarding where to build homes, urban planning, forest and watershed management, and the enforcement of construction standards all play a crucial role in determining whether a hazard becomes a manageable event or escalates into a full-blown disaster. Furthermore, social and economic disparities exacerbate the effects of hazards, leaving vulnerable Populations at a much higher risk compared to wealthier groups.

In the past, disaster management focused on responding to disaster rather than prevention. Governments and humanitarian organizations have primarily concentrated on deploying search-and-rescue teams, providing emergency aid, and rebuilding infrastructure after a disaster strikes. While these efforts save lives and offer immediate relief, they only address the aftermath of disasters rather than tackling the root causes. Post-disaster recovery tends to be costly, time-consuming, and often unsustainable, especially for developing countries with limited resources. This cycle of destruction, relief, and rebuilding highlights the shortcomings of a reactive approach.

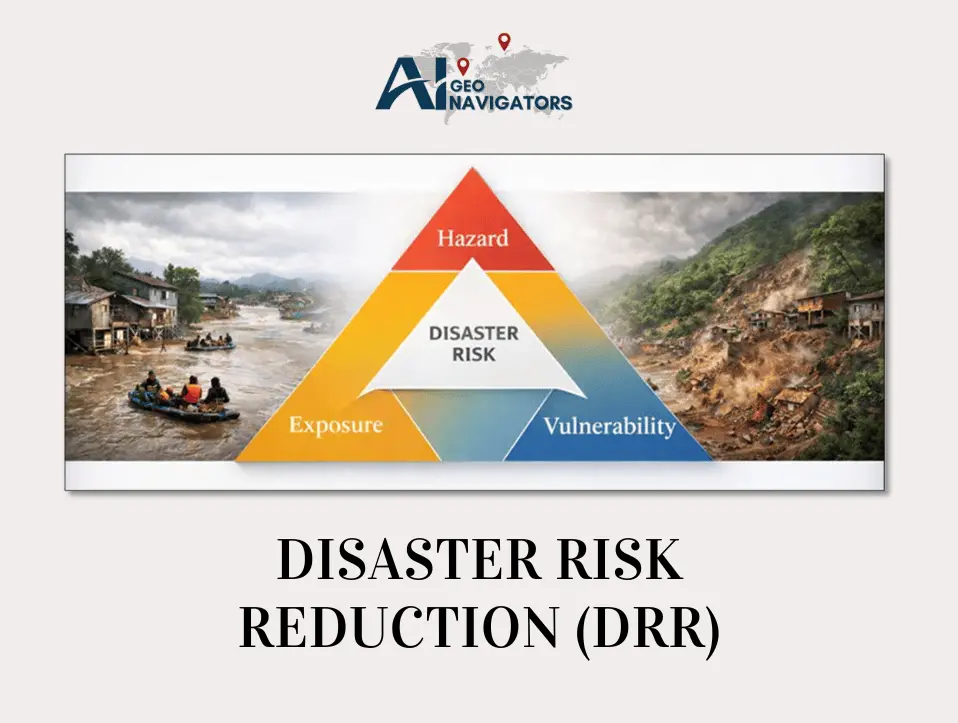

Figure 1: Increasing frequency and impact of natural disasters worldwide.

In contrast, Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) takes a proactive stance, emphasizing prevention, preparedness, and building resilience. DRR combines scientific knowledge, policy-making, community engagement, and sustainable development to minimize vulnerabilities before disasters hit. By focusing on reducing risks rather than simply responding to disasters, DRR helps societies save lives, reduce economic losses, safeguard development achievements, and create stronger, more resilient communities.

Globally, DRR has emerged as a vital strategy in disaster management, as seen in frameworks like the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, which advocates for a shift from disaster management to risk management. This framework prioritizes understanding disaster risk, enhancing disaster governance, investing in disaster resilience, and improving preparedness for effective responses. It emphasizes that successful risk reduction involves collaboration among governments, scientists, civil society, and local communities and must be multi-sectoral, inclusive, and continuous.

The repercussions of neglecting disaster prevention are evident in various case studies. For instance, the 2010 floods in Pakistan, affecting over 20 million people, were worsened by inadequate urban planning, deforestation, and insufficient flood management infrastructure. Similarly, the 2005 Kashmir earthquake exposed weaknesses in building construction, governance, and community readiness, resulting in tens of thousands of avoidable deaths. Conversely, countries like Japan, which heavily invest in earthquake-resistant structures, early warning systems, and community education, see notably lower casualty rates from similar-magnitude earthquakes.

DRR also aligns with sustainable development objectives. Without DRR, hazards can undo years of developmental progress in a short period. Schools, hospitals, roads, and farmland destroyed by disasters hinder human development indicators, increase poverty, and destabilize societies. By integrating risk reduction into planning, communities can safeguard their investments, ensure uninterrupted services, and bolster resilience against future hazards.

The significance of DRR is even more pronounced in the context of climate change, which amplifies the frequency and intensity of many natural hazards. With rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, glacier melting, and sea-level rise reshaping hazard landscapes, proactive prevention becomes even more crucial. In this evolving scenario, traditional response-focused strategies fall short; proactive, risk-informed planning and community involvement are essential to minimize losses and sustain development.

We will delve into the concept of disaster risk, the drawbacks of response-centric disaster management, and the numerous benefits of prevention through DRR. We will also explore key elements of DRR, its role in climate adaptation, and why proactive strategies are vital for building resilient societies. The evidence is clear: while emergency response remains important, prevention is more effective, compassionate, and sustainable than reaction alone.

Understanding Disaster Risk and the Concept of DRR

Disasters are not random events but rather complex outcomes of the interplay between natural threats, human presence, and community susceptibility. It is crucial to grasp these connections to fully appreciate the importance of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR).

Hazards are natural occurrences capable of causing harm, such as earthquakes, cyclones, floods, landslides, droughts, tsunamis, and heatwaves. While hazards are unavoidable, technological advancements have enabled the prediction and monitoring of many of these events. For instance, seismic networks can detect earthquakes early, and satellite systems can forecast cyclones and floods days ahead. However, disasters do not arise solely from hazards; the extent of their impact greatly depends on exposure and vulnerability.

Exposure involves the presence of people, infrastructure, and assets in hazard-prone areas. A city near a river faces a higher flood risk compared to one located further inland. Similarly, settlements on steep slopes are more susceptible to landslides. Factors like urban growth, migration trends, and population density influence exposure levels. Unplanned settlements along floodplains in Pakistan, for instance, have significantly raised exposure, turning moderate floods into devastating calamities.

Figure 2: Components of Disaster Risk (Hazard, Exposure, Vulnerability)

Vulnerability refers to the degree to which communities or systems are at risk, influenced by social, economic, environmental, and physical factors. Poverty, lack of education, substandard infrastructure, inadequate healthcare, and weak governance all contribute to vulnerability. During disasters, vulnerable groups like women, children, the elderly, and marginalized communities suffer disproportionately. For instance, the poorest populations in Pakistan were the hardest hit by the 2010 floods, experiencing high mortality rates and extensive asset losses.

Disaster Risk Reduction aims to lessen exposure and vulnerability, ultimately reducing potential losses. By identifying risks, vulnerable groups, and prevention strategies, DRR allows societies to proactively manage risks rather than merely react to disasters. It combines scientific knowledge, governance structures, community involvement, and sustainable development practices to enhance risk management capabilities. Countries that have embraced DRR have demonstrated its effectiveness. Japan’s investment in earthquake-resistant structures, tsunami warnings, and public education has significantly reduced casualties from earthquakes. Similarly, Bangladesh’s flood preparedness initiatives have lowered flood-related deaths despite high exposure to riverine flooding.

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 outlines key priorities for DRR, emphasizing the importance of understanding disaster risk, improving governance, investing in resilience, and enhancing preparedness. These priorities underscore that DRR is an ongoing, integrated process that should be ingrained in development planning, governance, and community engagement.

The significance of DRR is particularly evident in hazard-prone regions like Gilgit-Baltistan, where steep terrain, heavy rainfall, glacier melt, and seismic activity increase vulnerability to landslides, floods, and avalanches. Without proactive risk assessment and adequate measures, even minor hazards can lead to significant loss of life and property. Conversely, implementing DRR strategies like slope stabilization, flood monitoring, and public education can greatly reduce disaster impact and boost community resilience. DRR also advocates for sustainable environmental practices. Healthy ecosystems act as natural defenses against hazards, while environmental degradation heightens vulnerability. By preserving natural habitats, DRR not only reduces disaster risks but also contributes to climate resilience.

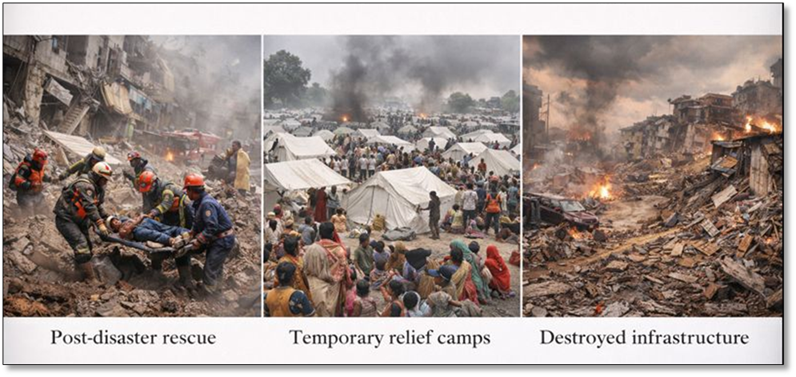

Limitations of a Response-Focused Disaster Management Approach

Traditional disaster management has long relied heavily on emergency response, but this approach has significant drawbacks. It mainly focuses on post-disaster activities like search and rescue, relief distribution, temporary shelters, and reconstruction. While these actions are crucial for saving lives and restoring basic services after a disaster, they do little to stop the disaster from causing extensive and often irreversible harm.

One major issue with a response-centric approach is its timing. Disasters like earthquakes or flash floods strike suddenly, leaving little opportunity for intervention. Even well-equipped emergency services can’t prevent immediate deaths during these events. The 2005 Kashmir earthquake, which claimed over 73,000 lives in Pakistan, highlighted the consequences of inadequate preparedness and delayed responses in remote areas.

Additionally, relying solely on response fails to safeguard infrastructure or economic assets from destruction. The 2010 Pakistan floods displaced millions and destroyed vital farmland, revealing that reactive measures alone cannot shield vulnerable communities, especially in rural or isolated regions. Emergency response and reconstruction efforts are also financially draining. The 2010 Pakistan floods incurred approximately $10 billion in damages, money that could have been saved through preventative actions like better flood infrastructure and early warning systems. Continuously rebuilding vulnerable structures not only squanders public funds but also perpetuates susceptibility to future disasters.

Figure 3: Reactive disaster response often comes after irreversible losses

Moreover, response-oriented strategies often overlook the root causes of disasters. Post-disaster relief typically doesn’t address issues like poor urban planning, deforestation, or weak governance, leading communities to rebuild in hazardous areas without addressing underlying vulnerabilities. Disasters also disproportionately impact marginalized groups, such as women, children, and low-income individuals, exacerbating pre-existing inequalities. Response systems sometimes fail to prioritize these populations, resulting in unequal access to aid and recovery initiatives.

Furthermore, response-centered strategies often neglect environmental factors that worsen disasters, like deforestation or unsustainable land use. Failing to consider these factors can lead to secondary risks and prolonged recovery periods. While emergency response is vital for saving lives in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, its shortcomings are evident. It’s costly, unsustainable, and reactive, often failing to prevent loss of life, economic harm, or social disparities. To break free from the cycle of repetitive disaster impacts, it’s imperative to focus on Disaster Risk Reduction, emphasizing prevention, preparedness, and resilience as the cornerstones of effective disaster management.

Why Prevention Through DRR Is More Effective Than Response

Disaster Risk Reduction places a strong emphasis on prevention as its core principle. While responding to disasters focuses on dealing with the aftermath, prevention works towards minimizing or eliminating risks before hazards strike, making it a more efficient and long-lasting approach.

The key benefit of prevention is its ability to save lives by taking action before hazards occur. Early warning systems, educating communities, mapping hazards, and planning evacuations empower individuals and communities to act promptly and avoid risks.

For instance, Bangladesh’s flood management program showcases the success of preventive measures. Despite facing frequent floods, the country has significantly reduced mortality through investments in flood shelters, early warnings, and community mobilization. In contrast, inadequate preventive measures in Pakistan’s Sindh region led to numerous deaths during similar flood events. Prevention also extends to health hazards. Effective disaster preparedness, including hygiene training and evacuation practices, helps prevent post-disaster disease outbreaks. This proactive approach avoids secondary health crises that often follow floods or cyclones.

In addition to saving lives, prevention offers economic benefits and protects assets. Disasters not only damage buildings and infrastructure but also disrupt livelihoods and economies. Investing in resilient infrastructure, sustainable land management, and hazard mitigation proves cost-effective in the long run. The World Bank estimates that every dollar spent on preventive measures saves four dollars in post-disaster recovery costs. Measures like strengthening embankments, enforcing building codes, and preserving natural buffers like mangroves have significantly reduced economic losses. For example, mangrove restoration in India and Bangladesh has mitigated storm surges, saving millions in damages.

Preventive DRR also safeguards agricultural productivity by implementing drought-resistant crops and better irrigation methods. In Pakistan, flood-resistant wheat varieties have minimized crop loss during monsoon floods, ensuring food security and protecting farmers’ livelihoods. Disasters can undo years of development progress in an instant by destroying schools, hospitals, roads, and utilities. Integrating DRR into development projects ensures they are resilient and sustainable, preventing setbacks in education and healthcare. For instance, earthquake-resistant schools in Japan continued functioning after seismic events, unlike poorly constructed schools in Nepal that collapsed during the 2015 earthquake. Preventive DRR enhances social resilience by reducing vulnerabilities through education, awareness, and community involvement. Inclusive measures, such as training women in emergency skills and engaging local leaders, empower all social groups and enhance collective capacity to respond to hazards.

Environmental conservation plays a vital role in preventive DRR by using natural ecosystems like forests and rivers as protective barriers against disasters. Integrating environmental protection into DRR reduces disaster intensity while promoting sustainability. For example, mangrove restoration in Pakistan’s coastal regions reduces vulnerability to cyclones while creating livelihood opportunities.

Core Elements of Disaster Risk Reduction

Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) involves various interconnected elements within a comprehensive framework, rather than a single activity. These elements collaborate to prevent disasters, lower vulnerability, and enhance resilience. It is crucial for communities, governments, and organizations to grasp and implement these core elements effectively to reduce disaster risk.

To begin with, risk assessment stands as the primary and essential element of DRR. It entails identifying hazards, analyzing exposure, and evaluating vulnerabilities to understand the likelihood and potential impact of disasters. A robust risk assessment forms the basis for targeted interventions to allocate resources where they are most needed. Hazard mapping, which utilizes tools like Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and satellite imagery, plays a key role in risk assessment. By accurately mapping flood-prone areas, landslide zones, and earthquake fault lines, hazard mapping enables local authorities to prioritize areas for necessary interventions and community evacuation planning.

Moreover, vulnerability assessment supplements hazard analysis by examining socio-economic, physical, and environmental factors that contribute to susceptibility. By combining data on hazards, exposure, and vulnerability, risk assessments offer a comprehensive understanding of disaster risk, enabling proactive planning. Preparedness and Early Warning Systems are another crucial element of DRR. Preparedness involves equipping communities and institutions with the necessary tools to respond effectively in the event of disasters.

This includes conducting emergency drills, public education campaigns, stockpiling relief materials, and establishing communication networks. Early warning systems are vital for preparedness as they monitor environmental indicators and provide advance notice to at-risk populations. For example, Bangladesh has implemented river gauge monitoring and mobile phone alerts in flood-prone regions, enabling timely evacuations and saving lives. Similarly, Japan has earthquake early warning systems that alert citizens before seismic waves hit, allowing for immediate protective actions.

Resilient Infrastructure is essential for reducing the physical impact of disasters and ensuring the continuity of essential services. Buildings, roads, bridges, and utilities must be designed or retrofitted to withstand location-specific hazards. Community Participation and Capacity Building are at the heart of DRR efforts. Engaging communities in planning and decision-making ensures that interventions are contextually appropriate and sustainable.

Capacity building involves training individuals and institutions to identify risks, prepare for hazards, and respond effectively, enhancing social resilience. Effective DRR also requires strong governance structures and supportive policies that integrate disaster risk considerations into various aspects of development planning and regulations. Encouraging multi-stakeholder collaboration is essential for successful DRR outcomes.

The Role of DRR in a Changing Climate

The impact of climate change on disaster risks worldwide emphasizes the critical importance of Disaster Risk Reduction. With rising temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, melting glaciers, sea-level rise, and extreme weather events, natural hazards are becoming more frequent, intense, and unpredictable. Simply relying on post-disaster response is no longer sufficient.

Climate change has significantly changed the landscape of hazards. Areas once considered safe are now prone to floods, droughts have worsened, and storms have grown stronger. Glacial retreat in northern Pakistan and the Himalayas has heightened the risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), threatening downstream communities. Sea-level rise has led to increased coastal flooding and saline intrusion, especially in low-lying regions like Sindh and Balochistan. Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) plays a crucial role in preparing for and adapting to these new hazard patterns. By incorporating climate forecasts into risk assessments and development plans, societies can implement measures to reduce vulnerability. For instance, using hydrological models and climate scenarios helps predict future flood-prone areas, guiding the construction of embankments, evacuation routes, and shelters for communities.

DRR is closely intertwined with climate adaptation, both aiming to lessen vulnerability and strengthen resilience against environmental changes. Climate adaptation strategies such as afforestation, wetland restoration, sustainable agriculture, and water management align with DRR goals. For instance, mangrove restoration along Pakistan’s coasts helps mitigate storm surges, provides livelihoods, and reduces poverty.

In the face of climate change, early warning systems have become even more crucial. Extreme weather events like cyclones, heatwaves, and flash floods are becoming less predictable. Utilizing advanced forecasting technologies alongside community readiness enables timely action. Tools like mobile alerts, sirens, radios, and social media are increasingly used to share early warnings, especially in remote areas. Ecosystem-based DRR underlines the importance of natural systems in reducing disaster risks. Wetlands absorb excess rainfall, forests stabilize slopes, and coral reefs and mangroves lessen storm surges. Preserving and restoring these ecosystems is a key strategy for climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction.

Communities are essential in climate-adaptive DRR efforts. Local knowledge combined with scientific forecasting enhances resilience. Training communities in risk mapping, climate-resilient farming, water conservation, and disaster response boosts preparedness. For example, in Gilgit-Baltistan, community-driven early warning networks have reduced casualties from landslides and glacial floods.

Conclusion

Managing disasters involves a shift towards Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), which focuses on prevention, preparedness, and resilience rather than just reacting after the fact. Although immediate emergency response is crucial for saving lives post-disaster, it doesn’t tackle the underlying causes of vulnerability or prevent future losses.

Measures like risk assessment, early warnings, sturdy infrastructure, community involvement, and environmental conservation not only save lives but also cut down on economic losses, boost social unity, and protect long-term progress. DRR becomes even more vital with the rise of climate change, which heightens the frequency and intensity of various hazards globally.

Examples from countries such as Japan, Bangladesh, and Thailand, along with insights from disaster-prone areas like Pakistan, show that proactive planning and community participation significantly lessen disaster impacts. By integrating DRR into development, governance, and climate strategies, societies can prepare for hazards, decrease vulnerability, and form resilient communities that can face current and future challenges. Ultimately, prevention isn’t just better than reacting; it’s a necessity. Investing in DRR ensures that disasters no longer disrupt lives, economies, or progress, providing a sustainable, fair, and resilient future for communities worldwide.