Pakistan stands at the frontline of the global climate crisis. Ranked consistently among the top ten most climate-vulnerable countries by the Global Climate Risk Index (Germanwatch, 2021), it faces mounting environmental challenges, from glacial melt in the north to flooding in Sindh and Balochistan.

In 2022 alone, Pakistan witnessed devastating monsoon floods that displaced over 33 million people and caused damages exceeding $30 billion (World Bank, 2023). These climatic disruptions demand not just policy reform, but sustained, community-focused advocacy and communication.

Table of Contents

TogglePakistan’s Climate Vulnerabilities

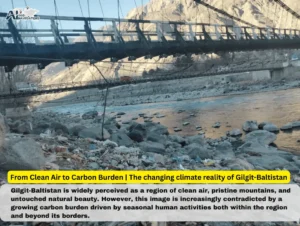

Geographically, Pakistan is home to over 7,000 glaciers—the most outside the polar regions. Accelerated glacial melt, driven by rising temperatures, has increased the frequency of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), threatening thousands of downstream communities (UNDP, 2022). Concurrently, recurring droughts in Tharparkar, heatwaves in Punjab, and sea-level rise along the coastal belt have pushed millions into cycles of poverty, migration, and food insecurity (IPCC, 2021).

These realities underscore the urgency of not only mitigation and adaptation but also communication strategies that translate data into public understanding and action. While policies like the National Climate Change Policy (2012) and the updated NDCs (Nationally Determined Contributions) are in place, the communication gap between scientific knowledge and grassroots awareness often hampers implementation (Government of Pakistan, 2021).

Lack of cultural awareness of climate change limits people’s ability to act.

According to my personal understanding, in many rural areas, weather surprises are explained through faith rather than science. for example, a sudden unseasonal rain-shower may be hailed as “Allah’s rehmat” (God’s mercy) instead of seen as a signal of climatic disruption due to lack of awareness and education.

This kind of interpretation highlights why communities lacking climate literacy often struggle to adapt: when emerging weather patterns are viewed as divine anomalies rather than ecological warnings, no responsive action is taken. Field studies have shown that many farmers in Pakistan report having “no awareness or direction” on how to deal with rising temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns (Ahmad, 2020).

Without scientific understanding that even a small temperature rise—such as 1°C—can destabilize ecosystems and livelihoods, preparedness remains minimal. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a rise from 1°C to 1.5°C in global temperatures could lead to severe consequences for water availability, crop yields, and food security (IPCC, 2021).

In Chitral, for instance, local elders recall winters that once brought three to four feet of snow, while in recent years, snowfall has nearly vanished (Ali et al., 2021). If such drastic changes are simply interpreted as “the will of God,” communities may miss the critical window for adaptation whether it’s adjusting cropping cycles or conserving glacial meltwater.

Therefore, communicators and climate advocates must bridge scientific knowledge with cultural context, sensitively aligning religious worldviews with ecological realities. By connecting the loss of Booni’s traditional snowfall or the premature arrival of spring rains to the broader discourse on climate change, awareness becomes action, and cultural belief becomes a pathway for resilience.

The Role of Advocacy and Strategic Communication

As the Communications Manager at AI Geo Navigators, I have come to understand that advocacy is most powerful when it is rooted in both evidence and empathy. Our team uses GIS and artificial intelligence to visualize climate risks, from real-time flood mapping to land use analytics. However, we’ve found that the true impact lies not just in data generation but in storytelling. By translating technical reports into visual narratives, animated explainer videos, and culturally contextualized messaging, we reach a broader, more diverse audience.

Effective climate communication is not a luxury, it is a necessity. For example, a study by Khan et al. (2022) found that over 60% of rural Pakistanis were unaware of local climate adaptation programs due to poor outreach. Similarly, Ahmed and Mustafa (2020) observed that policy uptake increased significantly in regions where community-led awareness sessions were held using vernacular media.

Through digital platforms, our campaigns at AI Geo Navigators aim to normalize discussions on climate resilience. We’ve launched social media series explaining concepts like urban heat islands and carbon credits, and collaborated with youth influencers and educators to amplify climate literacy.

In many high-risk, climate-sensitive regions where awareness is still limited, Geo AI Navigators aims to build local understanding of how even a one-degree rise in temperature can disrupt ecosystems and trigger severe hazards.

Through our initiatives and social media campaigns, we focus on empowering communities to recognize these risks, adopt early warning practices, and take ownership of localized climate monitoring and resilience strategies.

Influencing Policy and Behavior Through Advocacy

Pakistan’s success at COP27 where it led the Global South in pushing for the historic Loss and Damage Fund is a direct result of coordinated advocacy efforts led by civil society and communication strategists (Farooq & Nasir, 2023). This is proof that persistent storytelling through media, civil engagement, and diplomatic dialoguecan translate into institutional change.

In my previous role at Oxfam GB, I contributed to this landscape by co-developing community reports that highlighted gender-specific impacts of climate shocks. These reports were utilized to develop relevant and accurate content for Oxfam GB’s social media platforms and knowledge management repositories to raise awareness about climate change.

Furthermore, through participatory media training at AI Geo Navigators, we’ve engaged university students and development professionals to craft climate messages that resonate across rural and urban divides. As highlighted by Latif et al. (2021), such inclusive campaigns are key to changing behaviors—whether it’s encouraging water conservation in agriculture or mobilizing youth for clean energy advocacy.

The Way Forward

To ensure long-term sustainability, climate advocacy in Pakistan must:

- Be localized and inclusive: Engage communities using local languages and culturally relevant formats.

- Leverage data for impact: Use GIS and AI not just for analysis, but for storytelling.

- Institutionalize communication: Make strategic communication a mandated component of every climate program.

- Empower youth: Pakistan’s youth bulge is its strength. With 64% of the population under 30, the future lies in nurturing climate advocates through digital tools, education, and public speaking platforms.

Conclusion

Pakistan’s climate crisis is as much a communication challenge as it is an environmental one. As someone working at the intersection of climate communication, technology, and community engagement, I believe that advocacy must evolve from mere awareness to strategic influence.

With the right partnerships, inclusive narratives, and consistent public engagement, climate communication can shape policies, shift behaviors, and inspire resilience. It is only through a collective, communicative approach that Pakistan can move from vulnerability to adaptability—and from crisis to leadership in climate action.